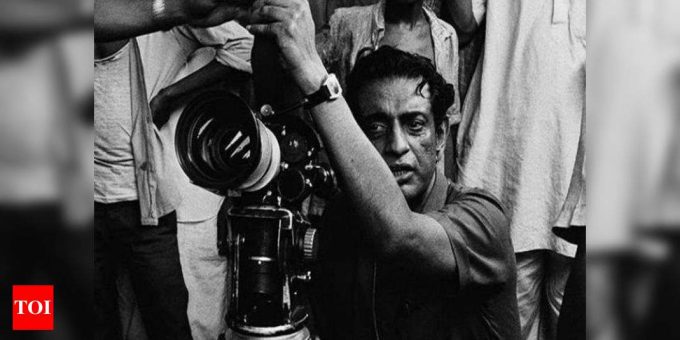

The year 2021 marks the birth centenary of renowned auteur, polymath, litterateur, composer, illustrator and designer, Satyajit Ray. There isn’t much unanalyzed about Ray’s film-making. His eye for perfection, poignancy, profound understanding of both the content and technique, coupled with his background scores, sets and costumes, are all a matter of awe and inspiration worldwide. His first film was Pather Panchali (1955), adapted from Bengali author, Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay’s eponymous 1928 novel. The film was apparently being made by a group of neophytes, who had to stop filming more than once, owing to the depletion of their shoestring budget.

* The financiers and producers were so apprehensive of Ray’s attempt, that he had to appeal to Dr. B.C. Roy, the then Chief Minister of Bengal, for funds.

What many people may not know is that even Dr. Roy remained unconvinced about the tragic and heart-breaking ending, and is said to have insisted on a lighter and happier one. The ending, however, remained unchanged, and is still considered one of the most logical and artistically accomplished endings in the annals of World Cinema. The film would eventually win the 1956 Cannes Special Jury Award as the ‘Best Human Document’, fifteen other international awards and establish Ray as the most feted Indian filmmaker.

·* So realistic was Ray’s imagery, that Pather Panchali raised a murmur of discord amongst his contemporaries in the film industry, who felt offended by ‘his exhibition of India’s poverty abroad’.

A paper clipping from the NY Times, April 24, 1991, wherein Ray’s passing was reported, said – “His Bengali-language films were in sharp contrast to the escapist and formula confections of music, dance, romance and violence of the vast Hindi-language film industry in Bombay.

His comparatively small audience forced him to adhere to minuscule budgets (rising to $100,000 from $40,000 over the decades) and to do much of the work himself. In addition to directing, he wrote scripts and music, designed sets, operated cameras, was sometimes the producer and even supervised advertising copy.”

Early life

To introduce Ray once again, is superfluous, but required just like the ‘Recap’ that often irks us, on our Netflix series. He was born on May 02, 1921 to Sukumar Ray and Suprabha, in Calcutta. Sukumar fell ill to Kala-azar the same year, a deadly and untreatable disease at the time, and passed away in 1923, when Satyajit, or Manik, as he was lovingly called, was barely two-and-a-half-years old.

* The absence of his father in physical form, would often be reflected in Ray’s early films, where the father figure remained inconspicuous for the best part.

Manik came to know his father primarily through his mother, and his own interpretation of his literary works, which were multifarious and pioneering. Ray Sr. was an accomplished poet, author, photographer, lithographer and publisher, widely credited for introducing non-sense poetry to the Bengali readers. His own father, famous author, philosopher, social reformer and amateur astrologer, Upendrakishore Roy Choudhury, had been an active member of the Brahmo Samaj, and had earlier founded a publishing house, which Sukumar kept alive and in good shape through his own lifetime, assisted by his brother, Subinoy. Upendrakishore Roy Choudhury purchased land, constructed a building at 100 Garpar Road, and the press ran right from their own house, for the most part of it. Famous children’s magazine, ‘Sandesh’ was introduced in 1913, thanks to that publishing house, U. Ray and Sons.

·* Satyajit Ray’s earliest fascination with artistry and its paraphernalia were most probably associated with this press.

Ray was the creator of fictional sleuth, Feluda, and an array of remarkable and likeable associates, both good and bad. Sandip, his son, has brought to screen many of his Feluda stories, albeit, Satyajit Ray directed two of the most widely known Feluda movies, Sonar Kella (1974) and Joi Baba Felunath (1979), himself. Ray also authored a collection of sci-fi stories featuring Professor Shonku, an absolutely likeable scientist with a penchant for novel inventions.

Marriage

In her book, ‘Manik and I’, Ray’s wife, Bijoya unraveled a chunk of their very ‘Bollywoodish’ love-story. Since she was older than Ray, and they were first cousins, their romance wouldn’t be taken well by their aristocratic and conservative Bengali families. After a courtship of eight long years, they got married at her sister’s house on October 20, 1948. It was a registered marriage, and both decided to keep it a secret till better times emerged. Eventually, keeping the actual fact under wraps, Satyajit could convince his mother Suprabha, that he would marry no one but Bijoya, and the families eventually conceded. They were married again with Bengali rituals on March 3, 1949.

·* Bijoya recounts, “I was overjoyed. After believing I would never be able to marry him, here I was, getting married twice!”

Satyajit Ray and his relationship with his actors and actresses

Amitava Nag’s book ‘Satyajit Ray’s Heroes and Heroines’ deals with a subject that is often overlooked. He analyses Ray’s portrayal and relationship to the characters that his actors played on-screen. While reading biographies of film personalities, we mostly read about their stardom and their real-life tribulations, and this book is a welcome relief in that sense.

For many hard-core Soumitra Chatterjee fans, the thespian, who recently passed away after an illustrious career stretching for nearly seven decades, if referred to as Ray’s Blue-eyed Boy, would be too unjust, considering his multi-faceted contributions to films, poetry, theatre, and arts in general. There is, nonetheless, no denying the fact that he was the most-repeated actor in fourteen out of Ray’s twenty-seven films. Tracing only his journey from the innocent and dreamy Apu in Apur Sansar (1959) to the victimised Dr. Ashoke Gupta in Ganashatru (1989) and the all-suffering Proshanto in Shakha Proshakha (1990), would provide a melange of Ray’s own realization and growth as a person, a filmmaker and a part of society at large. The roles for some of his other oft-repeated actors like Chhabi Biswas, Tulsi Chakraborty, Santosh Dutta, Utpal Dutta, Sharmila Tagore, Aparna Sen and Madhabi Mukherjee, were also chosen with such care that those on-screen characters have left behind indelible imprints on the minds of cine-goers.

* Ray’s eye for perfection could be understood if one observed how he chose diverse, yet radically dissimilar roles for Madhabi Mukherjee and Sharmila Tagore, who were as different as chalk and cheese. Similarly, how Ray chose superstar Uttam Kumar for only two of his movies, was another indicative of his understanding of the craft. Arindam Mukherjee of Nayak (1966) and Byomkesh Bakshi of Chiriyakhana (1967) couldn’t have been more dissimilar, and yet, they both required the effortless charisma and breathless credibility which only Uttam Kumar could lend…

Ray and his contemporaries

It is a well-known fact that Ray was said to have realized his passion for filmmaking after his chance meeting with French director, Jean Renoir, and on watching Vittorio De Sica’s neorealist film, ‘The Bicycle Thief’ (Italian: Ladri di biciclette, 1948). That he would one day be regarded so highly by some of the best directors of all times, Akira Kurosawa among them, was evidence enough, of how accomplished this self-taught man had been at his craft!

* Kurosawa believed that “Never having seen a Satyajit Ray film is like never having seen the sun or the moon.”

Ray’s mutual adulation for Kurosawa, Ingmar Bergman, Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola, Richard Attenborough, Michaelangelo Antonioni, Roman Polanski, Elia Kazan, Marlon Brando, John Hurt, among others, has often been reproduced on media through some of the most treasured stills, a bunch of interviews, and very memorable quotes they shared.

* Elia Kazan rightly said about Ray, “If he were in Hollywood, he would have proved a tough challenge for all of us.”

It is however, another well-known fact that Ray, in spite of having been invited there, refrained from venturing west, because the seemingly stifling process of filmmaking there, was in sharp contrast to his leisurely pace and novel framework.

Interestingly, how Ray was always pitted as an adversary, against his two contemporaries, the legendary Ritwik Ghatak and Mrinal Sen, was more of a media hype, than anything else. Sen even said in an interview that Ray and he were often engaged in constructive criticism of each other’s works.

Ray and his music

The all-rounder that he was, Ray composed the background scores for most of his films himself, which, he is said to have done primarily on his piano. Ustad Vilayat Khan who composed an excellent background track for Jalsaghar (1958) and Ustad Ali Akbar Khan whose unforgettable score for Devi (1960) took the film to an entirely different level, were both said to have been unhappy with Ray, for being too interfering and disregarding of their independence. Ray was however said to have found the perfect musical partner in sitar maestro, Pandit Ravi Shankar, who composed for ‘Pather Panchali’, ‘Aparajito’, ‘Apur Sansar’ and ‘Paras Pathar’. The soulful scores speak volumes about their conducive and mutually satisfying collaboration. Teen Kanya (1961), an adaptation of three of Tagore’s stories, was however, the official birth of Ray, the music composer, and he never looked back after that.

* That Ray generally chose Anup Ghosal to sing for his films, and Kishore Kumar to render the single timeless Tagore song, ‘Ami Chini Go Chini Tomare, O Go Bideshini’ in Charulata, may also give an insight to his understanding of musical subtleties and his pickiness, something that legendary showman Raj Kapoor also possessed.

Inspired Works

* Henrik Ibsen’s ‘The Enemy of the People’ was probably the only non-Indian work to be adapted to a Ray film. He also adapted two of Munshi Premchand’s stories, Shatranj ke Khiladi (1977) and Sadgati (1981).

Other than that, Ray had taken up famous works by not only Tagore, but by many Bengali authors like his own grandfather, Upendrakishore Ray Choudhury, Prabhat Kumar Mukhopadhyay, Rajshekhar Basu, among others.

Designer Satyajit

Satyajit Ray’s multi-dimensional talents have remained largely overlooked in favour of his filmmaking, however, he experimented with calligraphy and design throughout his life, most prominently for the Sandesh magazine. He is said to have developed four typefaces for Ray Roman, Ray Bizarre, Daphnis and Holiday, and many Bengali ones.

He had studied painting at the Kala Bhavan in Shantiniketan, and was mentored by greats such as Nandalal Bose and Benod Bihari Mukherjee. Ray preferred creating his publicity contents, the sketches accompanying his stories, and the covers of his books and was among the pioneering graphic designers of India.

* Ray even designed the cover of Bibhutibhushan Bandyopadhyay’s famous adventure novel, Chander Pahar!

Ray, his Oscar, and his legacy

Many of Ray’s films have been preserved at the Academy Film Archive for their seminal value to cinema, and he stands as the most influential and only Indian filmmaker to have received an Honorary Oscar for Lifetime Achievement in 1991. He was the recipient of the highest Indian civilian award, the Bharat Ratna, sometime before his passing the same year. He had been conferred with the Dadasaheb Phalke Award in 1985, and had won thirty-two National Film Awards, and remains only one of four directors to have won the Silver Bear in Berlin more than once. Ray also won many other international film awards, and also the Legion of Honour by the French President, in 1987.

If asked about Ray and his legacy, the first point to emerge would definitely be that one didn’t need to move out to more commercialized markets, in order to achieve international repute. The second would be his conviction to go by his own intuition, unfazed by even major setbacks like apprehensive financiers, angry criticisms, and a relatively smaller audience. The body of Ray’s works would remain an inspiration for generations to come, for their sheer simplicity, their avant-garde techniques, their apparent commercially lackadaisical nature, but the profound depth of understanding of the content. Ray remains the apocryphal one-man army, whose optimum adaption of western techniques, coupled with his deep-rooted Indian humility will be a hearty change in this fast age of glitz and glamour…