The basement condo in central Edmonton, where Luis Ubando Nolasco and his family carefully rebuilt a home and a life, is being emptied out.

The father, his wife Cinthya Carrasco Campos and their two young daughters are set to be deported to Mexico Monday. The family, who fled to Canada in 2018 in the wake of a family member’s homicide and ongoing threats, have been denied refugee status by the federal government.

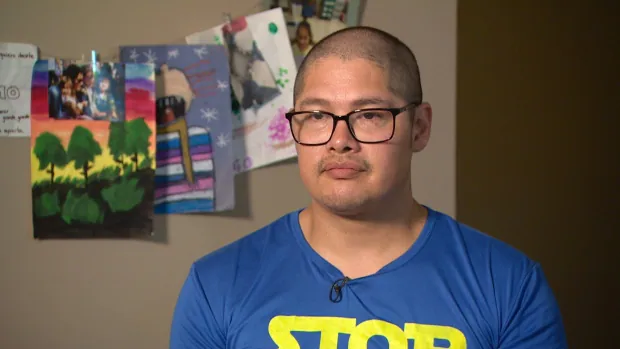

In preparation for deportation, the family has sold off much of their furniture. In the living room, the TV is on the floor and the family has cushions to sit on. The wall above where there used to be a couch is still crowded with children’s artwork and drawings.

The two girls are finishing up the year at their elementary school. As they enjoy end-of-year parties and field trips, their parents are desperately trying to delay or stop the return to Mexico.

Ubando Nolasco has even tried to convince authorities to send him back first, alone.

“If they can just stay, I’ll go back. I can go,” he told CBC News last week. “Make an example of myself. If they want to see somebody’s been murdered, I can go back and get murdered.”

Speaking through tears, the father shared his fears about what will happen to his children if they return to Mexico and are discovered by the people who, he says, have already killed his brother and are still actively looking for him.

“They will take my daughters, they will dismember them, and they will show me how they did that to my daughters,” Ubando Nolasco said. “That’s something that I don’t want to happen.”

On June 5, 2018, Ubando Nolasco’s brother, José Ubando Alvarez, told him someone was calling him and demanding money, according to federal court documents filed as part of the family’s case. Ubando Nolasco thought perhaps his brother was being targeted because of social media pictures he’d posted that gave the impression he was wealthy.

Ubando Nolasco said his brother laughed the threats off and sent mocking replies to their unknown source.

Two days later, on June 7, 2018, Ubando Alvarez was killed. He was shot multiple times, and police opened a homicide investigation that remains unsolved.

According to the documents, Ubando Nolasco provided evidence that, at his brother’s funeral, someone came up behind him, pressed something into his back and told him he would die unless he gave them money. He couldn’t see who it was, but soon began receiving threatening texts and calls demanding money.

Whoever was sending the threats to Ubando Nolasco started including details about Carrasco Campos and his two daughters as well. They knew where the girls were going to school.

The family went into hiding in Mexico before fleeing to Canada on a direct flight on July 11, 2018. Upon arrival in Vancouver, they obtained refugee protection.

There have been no arrests in connection to the brother’s death. Relatives and friends who have contacted the police to try to get more information have received pushback from police.

One relative even started receiving threatening messages, demanding to know the whereabouts of Ubando Nolasco. CBC News has viewed translated versions of those text messages, provided as part of the family’s refugee claim.

Arriving in Edmonton, the family settled into life as best they could under the circumstances.

The girls enrolled in school and, after a six month waiting period, the two parents were granted temporary work permits and got jobs. They’ve had to renew the permits annually but are still working — even with their deportation date just days away.

Denied refugee status

On Sept. 15, 2019, a three-member panel of the federal Refugee Protection Division heard the family’s claim for protection as refugees. According to written reasons for decision, the panel found that, while the threats the family faces are credible, they could take refuge in another part of Mexico.

Referred to as an “internal flight alternative (IFA)”, the panel suggested a region in a safer part of the country where it would be possible for the parents to find work.

The family argued that, in Mexico, student lists for schools are publicly available so it would be possible for a criminal group to track them down regardless of where they are.

The panel, however, found the family’s belief that whoever is making the threats would be able to find them is “speculative,” because the criminals’ identities are unknown, the amount of money they are seeking is unknown and the only motivation seems to be the alleged debt the brother owed the criminals.

The family appealed the decision. But in a February 2020 decision, the Refugee Appeal Division member upheld the panel’s decision.

“The existence of an IFA is fatal to any refugee claim. If a claimant can find safety from persecution by fleeing within their country, then they are not entitled to Canada’s surrogate protection,” wrote the member who rejected their appeal.

During their appeal, the family argued that it was “objectively impossible” for them to know the capacity or motivation of the people making the threats without knowing their identity.

In the written decision, the member who heard the appeal agreed, but found that, under Canadian law, the burden is on the appellants to show why the IFA isn’t a viable refuge for them, and that test hadn’t been met in this case.

The family sought a judicial review of the appeal decision, but that request was denied last September. Their counsel says they were notified in February.

As a last ditch effort, the family filed for humanitarian and compassionate leave to stay in Canada in April, but must return to Mexico in the meantime. The currently listed processing times are upward of a year.

The family has exhausted nearly all of their options.

With the help of a neighbour, who learned what was happening and stepped in, they’ve sought support from refugee support groups and met with staff from Edmonton Centre MP and federal Minister of Tourism Randy Boissaunault.

“We are actively looking into their cases and are in contact with colleagues at IRCC,” Boissonnault said in a statement via email.

Public campaign

Migrante Canada and its Alberta chapter have gotten involved in advocacy for the family.

“A public campaign is the only thing that we know of that can turn this around. Letting people know the stories out there, public pressure onto our political leaders — that is what we’re hoping would turn this around,” said Clarizze Truscott, vice-chairperson of Migrante Canada, who also sits on the Migrante Alberta executive.

Migrante Alberta is also in the midst of a campaign to stop another family from being forced to leave Canada: an undocumented single mother, who has a six-year-old Canadian daughter with health issues, is being deported to the Philippines.

They don’t have hard numbers, but Truscott said the organization is hearing from an increasing number of people who have suddenly been given deportation dates for June and July.

She said it’s baffling that the federal government is removing people while at the same time expanding the temporary foreign worker program.

“We’re removing them while opening the doors for a new set of workers with the same kind of temporary permits, essentially,” she said. “Why not keep the ones that are here? They have proven they belong to Canadian society.”

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada cannot comment on specific cases without written consent due to privacy legislation, said department spokesperson Rémi Larivière.

All eligible asylum claims receive an independent and fair assessment of their claim through the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, he said. For those not normally eligible to become permanent residents through regular programs, or who have exhausted all other options, an application on humanitarian and compassionate grounds is available.

“Every individual facing removal is entitled to due process, but once all avenues to appeal are exhausted, they are removed from Canada in accordance with Canadian law,” Larivière said.

Minister Sean Fraser has been mandated to build on existing pilot programs to explore ways of regularizing status for undocumented workers and the IRCC looks forward to continuing this work, he said.

Seeking peace

If Ubando Nolasco’s family ends up back in Mexico, they will likely have to hide and try to seek refugee status in another country, hoping to get what they thought they’d found in Canada — a normal life where their daughters will be safe.

“We came here to give — to be safe — but we’re not here to take,” he said.

He recognizes there are many people seeking to remain in Canada, and that the government is in a difficult position.

He doesn’t want special treatment, but he wants people to understand the danger his family is facing. That’s why he and his wife decided to share their identities, despite being fearful of what going public — and then returning to Mexico — could mean.

“This is to give my daughters an opportunity to live in peace,” he said. “They are worth every single second of effort that I can make.”