AMMAN: Few things encapsulate the Palestinian identity quite like the humble olive tree. It roots an entire nation to a land and livelihood lost to occupation, while serving as a potent symbol of resistance against the territorial encroachment of illegal settlements.

In the balmy Mediterranean climate of the Levant, olive trees have for centuries provided a steady source of income from the sale of their fruit and the silky, golden oil derived from it.

To this day, between 80,000 and 100,000 families in the Palestinian territories rely on olives and their oil as primary or secondary sources of income. The industry accounts for about 70 percent of local fruit production and contributes about 14 percent to the local economy.

It is perhaps no surprise, then, that these hardy trees feature so prominently in Palestinian art and literature, even in the far-flung diaspora, as symbols of rootedness in an age of displacement, self-sufficiency in times of hardship, and peace in periods of war.

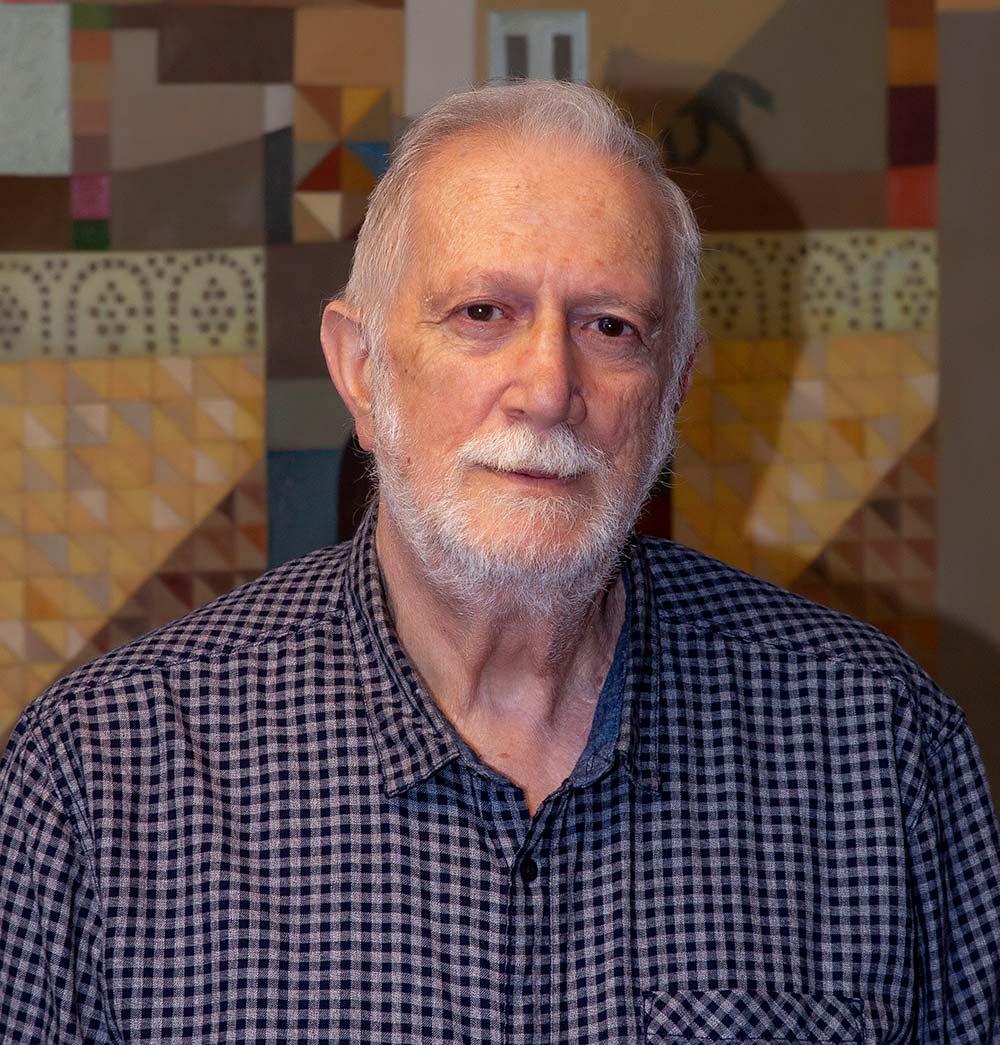

“It represents the steadfastness of the Palestinian people, who are able to live under difficult circumstances,” Sliman Mansour, a Palestinian painter in Jerusalem whose art has long focused on the theme of land, told Arab News.

“In the same way that the trees can survive and have deep roots in their land so, too, do the Palestinian people.”

Mahmoud Darwish, the celebrated Palestinian poet who died in 2008, sprinkled his works with references to olives. In his 1964 poetry collection “Leaves of the Olive Tree,” he wrote: “Olive is an evergreen tree; Olive will stay evergreen; Like a shield for the universe.”

Such is the economic and symbolic power of the olive tree in Palestinian national life that the rural communities that have tended these crops for generations are routinely targeted by illegal settlers attempting to denude families of their land and living.

Since the olive harvest began on Oct. 12 this year, observers in the West Bank have reported Israeli settlers attacking Palestinian villages on an almost daily basis, beating farmers, spraying crops with chemicals and uprooting olive trees by the hundreds.

FASTFACTS

* The land around the Sea of Galilee was once the world’s most important olive region.

* The area was the site of the earliest olive cultivation, dating back to 5,000 B.C.

* Southern Spain and southeastern Italy are now the biggest olive-oil-producing regions.

Such violence and vandalism is nothing new. The International Committee of the Red Cross said more than 9,300 trees were destroyed in the West Bank between Aug. 2020 and Aug. 2021 alone, compounding the already damaging effects of climate change.

“For years, the ICRC has observed a seasonal peak in violence by Israeli settlers residing in certain settlements and outposts in the West Bank toward Palestinian farmers and their property in the period leading up to the olive-harvest season, as well as during the harvest season itself in October and November,” Els Debuf, head of the ICRC’s mission in Jerusalem, said recently.

“Farmers also experience acts of harassment and violence that aim at preventing a successful harvest, not to mention the destruction of farming equipment, or the uprooting and burning of olive trees.”

According to independent observers appointed by the UN, the violence attributed to Israeli settlers against Palestinians in the West Bank has worsened in recent months amid “an atmosphere of impunity.”

In response to these attacks, Palestinian farmers have been forced to plant about 10,000 new olive trees in the West Bank each year to prevent the region’s 5,000-year-old industry from dying out.

Nabil Anani, a celebrated Palestinian painter, ceramicist and sculptor, believes the olive tree is a powerful national symbol that must be protected at all costs.

“For me it is both a national and artistic symbol; it reflects the nature and beauty of Palestine,” Anani, who is considered one of the founders of contemporary Palestinian art, told Arab News. “Our traditions, culture, poems and songs are often centered around the tree.”

To the west of Ramallah, the administrative heart of the Palestine government, Anani said the hillsides bristle with olive trees as far as the eye can see.

“They cover entire mountains and it is one of the most pleasant views that anyone can observe,” he added.

INNUMBERS

* 48% – Proportion of agricultural land in the West Bank and Gaza devoted to olive trees.

* 70% – Share of total fruit production in Palestine provided by olives

* 14% – Contribution of olives to the Palestinian economy.

* 93% – Proportion of the olive harvest used to make olive oil.

The late Fadwa Touqan, one of the most respected female poets in Palestinian literature, saw olive trees as symbols of unity with nature and of hope for the renewal and rebirth of Palestine.

In a 1993 poem, she wrote: “The roots of the olive tree are from my soil and they are always fresh; Its lights are emitted from my heart and it is inspired; Until my creator filled my nerve, root and body; So, he got up while shaking its leaves due to maturity created within him.”

More than just a source of income and artistic inspiration, however, olives also form a vital part of the Palestinian diet and culinary culture. Pickled olives feature in breakfasts, lunches and dinners, providing significant nutritional health benefits.

Olive oil, meanwhile, is used in scores of recipes, the most popular of which is zaatar w zeit: fluffy flatbread dipped in oil and then dabbed liberally in a thyme-based powder that includes sesame seeds and spices.

Beyond the dinner table, olive oil historically has had many other uses: As a source of fuel in oil lamps, a natural treatment for dry hair, nails and skin, and even as an insecticide.

It is not only the fruit and its oil that the olive tree contributes to the cultural and economic life of Palestine. Olive pits, the hard stones in the center of the fruit, have long been repurposed to make strings of prayer beads used by Muslims and Christians alike.

As for the leaves and branches of the trees, they are trimmed during the harvest season to be used as feed for sheep and goats, while the broad canopy of the olive grove provides animals and their shepherds with welcome shade from the relentless afternoon sun.

The wood of felled trees has also been widely used in the carving of religious icons as far back as the 16th century, and as a source of firewood before the modern profusion of gas. In fact, the glassmakers of Hebron, who are famed for their stained glass, continue to use charcoal derived from olive trees to fire their kilns.

While the quantifiably beneficial uses of the olive tree are many, perhaps what is even more valuable to Palestinians is the inspiration it has provided to poets, painters and prophets down the ages, not to mention the special place it continues to occupy in their culture and quest for statehood.

—————

Twitter: @daoudkuttab