Image copyright

Getty Images

Women from all age groups are protesting against the citizenship law in Shaheen Bag

For more than two weeks, hundreds of Muslim women have been braving one of the coldest winters in India’s capital Delhi to protest against a controversial new citizenship law. BBC Punjabi’s Arvind Chhabra reports.

On 31 December, Delhi experienced its coldest day in more than a century. But that did not deter the women of the Shaheen Bagh neighbourhood. Armed with thick blankets, warm cups of tea and songs of resistance, they have not left their spot under a tent on a public street since 15 December.

And that’s how they rang in the New Year – a few minutes after midnight, they stood up to sing the Indian national anthem.

Their demand? Revoke the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA). The law, which came into effect on 11 December, offers amnesty to non-Muslim immigrants from Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan. The Bharatiya Janata Party-led government says it will protect religious minorities fleeing persecution in these countries.

But the government’s words have done little to reassure India’s Muslims, many of whom fear the law will discriminate against them – and could even go as far as to push some out of the country or into detention centres.

“I hardly ever leave my house alone,” admits Firdaus Shafiq, one of the protesters. “My son or husband accompany me even to the nearby market. So I found it tough at first to be out here.

“But I feel compelled to protest.”

And it is women like Firdaus Shafiq who make the protest at Shaheen Bagh so unusual, according to activists and commentators.

Firdaus Shafiq says women need to come out from their houses to protest

“These women are not activists,” says Syeda Hameed, founder of Delhi-based Muslim Women’s Forum.

Instead, they are ordinary Muslim women, many of them homemakers, at the centre of a national debate – standing up to the government.

“This is the first time they have come out on a national issue which cuts across religious lines and I think that’s important,” says Ms Hameed. “Although it’s something to do with victimisation of [the] Muslim community, it’s still a secular issue.”

Read more about the citizenship law

It’s hard to say how many women were present when the protest started but their numbers have swelled quickly. They first came out on the night of 15 December – when a protest by students of Delhi’s Jamia Millia Islamia university ended in clashes with the police. The university said police later entered the campus without permission and assaulted staff and students.

The protests against the act snowballed after that night, spreading out across the country.

While many protests have come and gone, and some have descended into violence, the site in Shaheen Bagh has remained consistently occupied and peaceful.

But as it sits on the border between eastern Delhi and Noida, a suburb, and serves as a crucial link for commuters, not everyone is happy.

“It’s affecting our business,” a local shopkeeper says, while a resident who works in Noida says it now takes him double the time to get to work. Protesters say they don’t want to disrupt anyone’s life and have pledged to keep their sit-in peaceful.

Yet other shopkeepers have come out in solidarity – some have even turned up with food. In fact, as the protest has grown, it has drawn people from across the city, from students to political commentators.

Media playback is unsupported on your device

“We want to ensure that this protest doesn’t turn violent and that we don’t give the police a chance to use force against us,” one protester, who did not wish to be named, says.

“We’ve been forced to protest because of the government,” Ms Shafiq adds. “If we fail to prove our citizenship, we would either be put into a detention centre or banished from the country. So it’s better to struggle for our rights now.”

Her words echo the concerns of many others, who fear the CAA could endanger their citizenship if it is used in conjunction with the National Register of Citizens (NRC).

This is because the NRC will eventually require Indians to submit documents proving their citizenship. But while non-Muslims who are not on the register could claim protection under the CAA as a minority, Muslims without the required paperwork do not have the same rights and could be detained or deported.

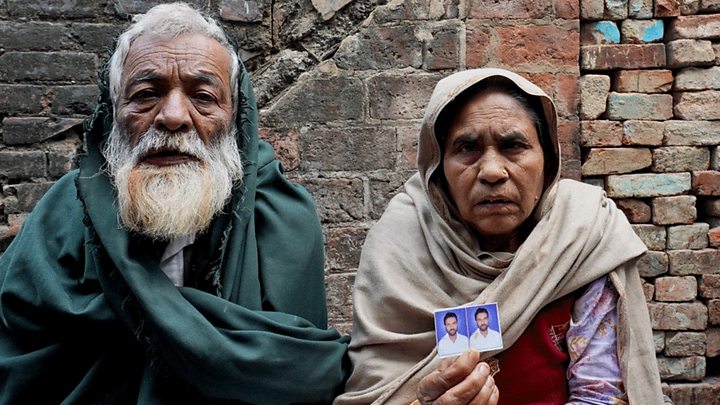

Image copyright

Getty Images

The cold weather has not deterred the protesters

And even though the government has said it has no immediate plans to implement a nationwide NRC, protests have continued – with some of the women so dedicated to the cause that they have temporarily given up work.

Rizwana Bani, a daily wage labourer, says that she is losing pay by being here day and night, but is also scared of what the law could entail for her and her family.

“We don’t know where and how to get those documents, which will prove our citizenship,” she says. “We’re being divided on the basis of religion. We are Indians first and then, Hindus or Muslims.”

The protest has also drawn women of all ages.

“I won’t leave this country, and I don’t want to die proving I am Indian,” says 70-year-old Aasma Khatoon, who hasn’t left the protest site for days.

Humaira Sayed feels other communities also need to join the protest

“It’s not just me. My ancestors, my children and grandchildren – we are all Indian. But we don’t want to prove this to anyone.”

Protesters say that the law as they see it targets Muslims, but is a threat to everyone else too.

“The law violates the constitution,” says Humaira Sayed, a university student. “It may target Muslims at the moment but we’re convinced it will gradually target other communities too.

“As a Muslim I know I’ve to be here for my brothers, sisters , the community and for everyone else.”

Credit: Source link